Home » Chemistry Degree Programs at Western Oregon University » Student Activities » Chemistry Corner » Which Diet is Right for You? » The Ketogenic Diet

MenuWhich Diet is Right for You

high fat, high controversy: The KetoGenic Diet

By Jennifer Vahl

Section 1: What is the Ketogenic Diet?

Section 2: Sample Diet Plan

Section 3: What Do the Studies Show?

Section 4: References

Section 1: What is the Ketogenic Diet?

The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, moderate-to-low protein, low carbohydrate diet. It is intended to mimic the metabolic response to fasting and shift the body towards metabolizing lipids rather than glucose. Originally developed in the 1920s to treat epilepsy in children, multiple versions exist today, including the medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) keto diet (preferentially choosing medium-chain triglycerides as the fat source, typically from coconut oil). (Wheless, 2008) Protein is recommended at 0.8 to 1.2 (average of 1) gram per pound of body weight per day, and no more than 20 g of total carbohydrates per day. However, some variations of this diet allow for up to 50 g of carbohydrates per day. The majority of calories come from fat, between 70% and 90+%. People following the ketogenic diet, particularly children following it for neurological reasons, must take supplements daily as this diet can fail to provide all necessary micronutrients and fiber. (Allen et al, 2014) Some followers of this diet suggest maintaining a constant calorie deficit, but others recommend against counting calories and the ketogenic diet is often known for avoiding calorie-counting.

Section 2: Sample Diet Plan

A 140-lb female would need approximately 125-140 grams of protein per day (500-560 calories), 20 grams of carbohydrates (80 calories), and the remainder of her caloric needs from fats. A woman aiming for 1,900 calories a day might have the following typical day. A woman aiming for a reduced calorie intake for weight loss would eat a similar ratio of fat to protein to carbohydrates, but would eat reduced portions or use lower-calorie replacements for ingredients. Diet plans are easily modified for men allowing for differences in body weight.

Breakfast: Mushroom omelet

3 eggs

3 mushrooms

1 oz shredded cheese

Butter

43g fat, 25g protein, 4g carbohydrates, 490 calories

Lunch: Caesar salad

Iceberg lettuce

6 oz rotisserie chicken

1 oz Parmesan cheese

2 tbsp Caesar dressing

31.1g fat, 63g protein, 2.2g carbohydrates, 553 calories

Dinner: Chicken breast with herb butter and vegetables

1 chicken breast

¼ oz olive oil or butter for cooking

Herb butter: 1.25 oz butter + chopped garlic + fresh herbs

6 oz green beans

8 oz leafy greens

64g fat, 63g protein, 3g carbohydrates, 850 calories

Snacks: nuts, beef jerky, cheese

Total calories: 1,893 + snacks

Section 3: What Do the Studies Show?

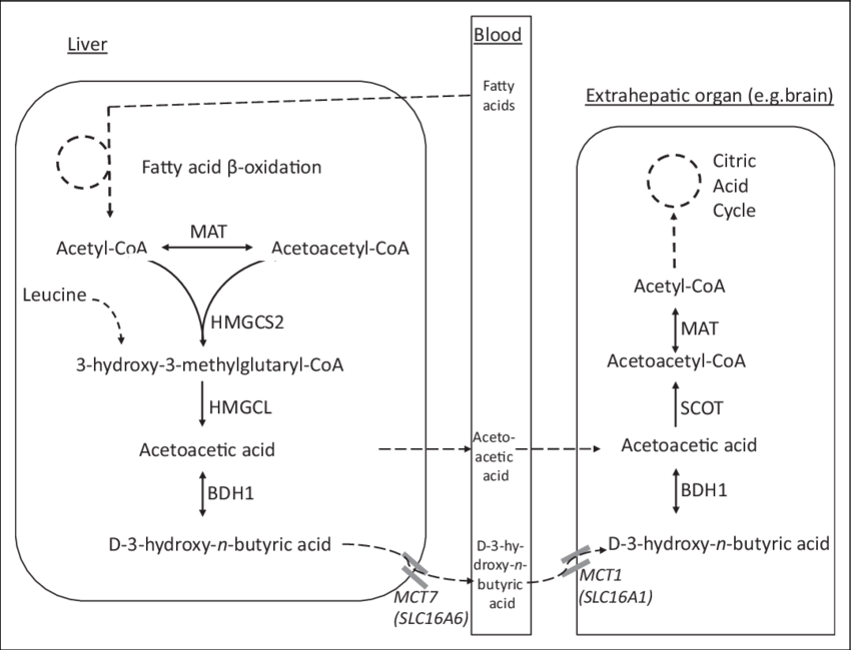

As the body runs low on glucose from dietary carbohydrates, the brain and CNS continue to need fuel. The body produces acetoacetate, acetone and beta-hydroxybutyric acid, commonly known as ketone bodies. These can be metabolized in the tissues in a stepwise manner back to acetyl-CoA for energy. (Paoli et al, 2013)

Figure 1. Ketone body metabolism and transport. Sass and Fukao et al, 2018.

Ketogenic diets tend to show significant weight loss in early stages (Foster, 2003). Many positive outcomes are seen in short-term interventions or regimens, whereas past the 12-month mark, the ketogenic diet appears to become either less beneficial or unsustainable in both mice and humans (Foster et al, 2003; Ellenbroek et al, 2014; Axen, 200). Results seen on a very low caloric ketogenic diet (VLCKD) seem to display a trend of greater success than unrestricted energy ketogenic diets for weight loss, however, many of the biological markers such as cholesterol, glucose and insulin response, and particularly the response observed in diabetic patients, occur in both the calorie-restricted and unrestricted diets, suggesting that perhaps the improvements in glucose metabolism are not solely caused by weight loss due to a caloric deficit. Eric Westman, in his 2003 review of ketogenic diets, summed up the conflicting results neatly, noting that while the general findings suggest short-term weight loss is favorable, many “out-patient clinical studies and in-patient laboratory studies concluded that there were insufficient data to dismiss or recommend the VLCKD for weight loss.”

For athletes or those looking to exercise to increase their weight loss, the ketogenic diet provides negligible benefits, if any. While exercise may become less strenuous considering a quick, short-term weight loss, patients on a ketogenic diet actually reported increased fatigue and exertion during exercise (REF). Since a true ketogenic diet has a low to moderate amount of protein, it is reasonable to speculate that it may not provide muscle tissue with the necessary components to rebuild after resistance training. Multiple studies have confirmed increased fatigue among people on a ketogenic diet (Urbain 2014), speculated to be exacerbated by one of many mechanisms, including a regulatory cascade with impacts on serotonin transmission and a mechanism that leads to increased ammonia buildup. (Vargas et al, 2018). The same authors who gathered these results conducted their own study on the impact of the ketogenic diet on body composition among athletic adult humans. Subjects on either a ketogenic or standard diet who exercised lost total body fat and visceral fat, but only the patients on the standard diet who exercised saw an increase in lean muscle mass.

Another human trial, this time in women who were not already used to strenuous exercise, found that the ketogenic diet and exercise combined decreased body fat but did not impact lean body mass. Their contrasting group, who exercised on a conventional diet, increased their lean body mass without significantly impacting their body fat mass. These results suggest that the ketogenic diet may not be a strong choice for anyone who prioritizes athletic performance or visibly toning up as they lose weight.

Although conflicting results exist, both HDL and LDL generally increase significantly for patients on a ketogenic diet (Bezerro Bueno et al, 2013), total TAGs in the serum generally slightly decrease and some studies report an overall “favorable” response to the ketogenic diet. In a short-term study of obese adults found that following a closely calculated regimen of ketogenic nutrition drinks improved their blood lipid profile (Choi et al, 2018) and a long-term (24-week) study of obese adults on a ketogenic diet found a reduction in LDL at the end of the treatment (Dashti et al 2004). However, results like these remain relative outliers and the general agreement is that the keto diet causes a significant increase in LDL due to simple increased intake of dietary fat. For people concerned about their cholesterol, digging deeply into results like this may be unappealing when considering that many alternative standard and low-fat or plant-based diets are well-shown to significantly reduce LDL and be generally “heart-healthy”.

The ketogenic diet is a natural option for patients with diabetes, pre-diabetes or metabolic syndrome to consider, as their carbohydrate intake is of increased interest to them. Their resistance to insulin means their muscles are less able to take up glucose, and will divert much of it to be stored in fat tissue. The results on a ketogenic diet are generally very favorable – when glucose levels are very low, many of the symptoms of insulin resistance are alleviated (Paoli et al, 2013). A review of multiple ketogenic diet studies concluded that diabetic patients generally experience “weight loss, improved insulin sensitivity, fewer fluctuations in blood glucose, and fasting lower blood glucose levels.” (Brouns 2018). The author goes on to note a common controversy in examining this diet, and speculates that many of these effects could be coming from the short-term weight loss this diet is notable for. He goes on to note that another meta-analysis of ketogenic diets published in a similar timeframe also found positive effects on symptoms of diabetes and insulin resistance, but interpreted the evidence to suggest that decreased appetite due to eating more protein and fat was leading to the weight loss that caused the beneficial gains. Since a number of the studies mentioned in this blog found greater differences between calorie-restricted and unrestricted groups than with high-carb and low-carb groups, this seems like a very reasonable question for so many researchers to still be asking.

Of further interest to diabetics, pain and loss of function associated with neuropathy from diabetes can be alleviated with the ketogenic diet. (Ruskin et al, 2009). A more recent study using mice with induced diabetic symptoms found that not only did mice on a ketogenic diet fail to develop mechanical allodynia (oversensitization to physical pain), but that introducing the keto diet to standard-diet mice could reverse the allodynia they had already developed. (Cooper et al, 2018).

Similar to the attention paid to the ketogenic diet for diabetic and pre-diabetic patients because of its strong effect on glucose as it mimics fasting, the diet has received scrutiny for its theoretical impact on cancer. Increased glucose metabolism is common in cancer cells (Annibaldi 2010), and a diet that restricts glucose intuitively is an attractive choice. Multiple mechanisms are speculated for how this impact may be achieved, beyond simply “starving” a tumor of glucose. Pyruvate, the end product of glycolysis before being metabolized further, reacts with toxic superoxides and peroxides directly, and reducing the availability of this may put tumor cells under oxidative stress. Similarly, the ketogenic diet reduces the substrates entering the pentose phosphate pathway to form NADPH necessary to reduce hydroperoxides, causing oxidative stress as well. Alternatively, the keto diet forces cancer cells to switch to mitochondrial metabolism, which is speculated to become dysregulated in cancer cells, also placing them under greater stress than surrounding non-cancerous cells. (Allen et al, 2014) Furthermore, the insulin/IGF-1 factor is implicated in tumor growth and is impacted by the amount of glucose in the diet (Paoli 2013)

In 1987, M.J Tisdale found decreased tumor growth in mice on a ketogenic diet, and many studies since have found at least some effect. Ketogenic diets have been found to improve survival rates of patients with colon, gastric and prostate cancer, and may enhance the effects of both chemotherapy and radiation. (Allen et al, 2014) A study exploring the impact of the keto diet on glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer, found a significant reduction in tumor growth rate and an increased survival rate among their ketogenic-fed mice, correlated neatly with the decreased blood glucose levels in the mice. (Morscher et al, 2015). The tumor cells that they examined showed a distinct inability to adapt to the dietary changes – a promising detail, as cancer cells are notorious for adapting quickly.

The KD has varied in popularity among epileptic patients as other treatments have been introduced, but it remains in use today and remains popular for patients with intractable epilepsy. Frequency of seizures is significantly reduced, and neurological functions such as cognition and memory improve. (Rogovik, 2010). When originally developed, it was thought that the ketone bodies produced were the source of the beneficial effects seen in epileptic patients, but later research showed that the ketone bodies alone weren’t accounting for the neurological changes. Since the brain uses more glucose during an epileptic seizure and high blood glucose may be connected to more frequent seizures, it was suggested that the reason both calorie restriction, fasting and the ketogenic diet showed some success with some epileptic patients was because it either stabilized blood glucose levels or that the brain’s shift from glucose metabolism to ketone body metabolism allows it to sidestep the glucose-seizure trigger. A study that was designed to explore this idea measured plasma glucose levels and ketone bodies in model epileptic mice who were fed either a calorie-restricted or unrestricted diet that was either a “standard” ratio of fats/proteins/carbs or a 75:14:12 ketogenic diet. Both calorie-restricted groups saw a significant reduction in blood glucose levels and weight compared to the standard diets, and the reduction was very similar between the standard-restricted and the ketogenic-restricted diets. Tellingly, both groups that had unrestricted calorie intake continued to experience the same frequency of seizures, while both calorie-restricted groups had a significant reduction, suggesting that the reduction in glucose is more important than the production of ketone bodies. (Mantis et al, 2004)

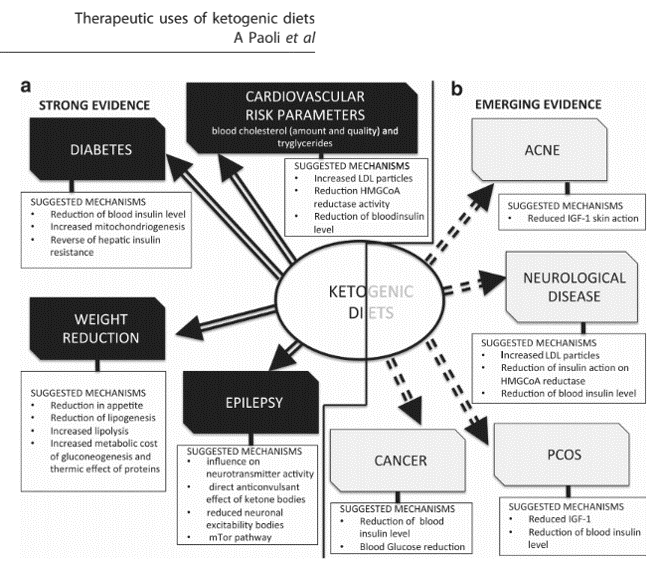

While long-term weight loss/maintenance and LDL levels remain a particular concern for those considering the ketogenic diet, it has strong evidence that it may help certain subsets of patients. Because it causes quick weight loss which immediately has its own effects on the body, attempts to pin down the metabolic effects of the diet have inconsistent success. A Paoli nicely summarizes issue in his his 2012 paper “Beyond weight loss: a review of the therapeutic use of very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets”, noting that principles as well-accepted as the first law of thermodynamics lead many to consider the source of their calories to be “irrelevant.” As the title of his paper implies, however, looking “beyond weight loss” can provide insights to the value of the ketogenic diet, and he summarizes the evidence for these effects nicely.

Fig 2. Biological Effects of the Ketogenic Diet. Paoli, et al

For many, the relatively predictable short-term weight loss and improved management of diabetes or epilepsy symptoms may be a strong factor for considering the ketogenic diet. For the general population looking to maintain their health, the lack of strong long-term research on weight loss, impactful (if not entirely clear) effect on LDL and cholesterol, and the difficulty of staying on the diet may be red flags.

Section 4: References

Allen B, Bhatia S, et al. 2014 Aug 7. Ketogenic diets as an adjuvant cancer therapy: history and potential mechanism. Redox Biology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2014.08.002

Axen K, 2010 Aug. Longitudinal adaptations to very low–carbohydrate weight-reduction diet in obese rats: body composition and glucose tolerance. Obesity. DOI: 10.1038/oby.2009.466

Brouns, F. 2018 Jun. Overweight and diabetes prevention: is a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet recommendable? Eur J Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1636-y

Choi H, Kim J. 2048 Dec 3. Two-Week exclusive supplementation of modified

ketogenic nutrition drink reserves lean body mass and improves blood lipid profile in obese adults: a randomized clinical trial. Nutrients. doi: 10.3390/nu10121895.

Cooper M, Menta B. 2018 Aug. A ketogenic diet reduces metabolic syndrome-induced allodynia and promotes peripheral nerve growth in mice. Exp Neurol. DOI 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.05.011

Ellenbroek J, van Dijck L, et al. 2014 Jan 7. Long-term ketogenic diet causes glucose intolerance and reduced beta and alpha-cell mass but no weight loss in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00453.2013.

Foster G, Wyatt H, et al. 2003 A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet for obesity. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa022207

Jabbek P, Moe I, et al. 2010 Jul 17. Resistance training in overweight women on a

ketogenic diet conserved lean body mass while reducing body fat. Nutr Metab. DOI: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-17

Mantis J, Centeno N. 2004 Oct 19. Management of multifactorial idiopathic epilepsy in EL mice with caloric restriction and the ketogenic diet: rule of glucose and ketone bodies. Nutr Metab. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-1-11

Morscher R, Aminzadeh-Gohari S, et al. 2015 Jun 8. Inhibition of neuroblastoma tumor growth

by ketogenic diet and/or calorie restriction in a CD1-Nu mouse model. PlOS ONE. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129802

Paoli A, Rubini A. 2013 Jun 6. Beyond weight loss: a review of the therapeutic uses

of very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets. Eur J Clin Nutr. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2013.116;

Urbain P, Strom L, et al. 2017 Feb 20. Impact of a 6-week non-energy-restricted ketogenic diet on physical fitness, body composition and biochemical parameters in healthy adults. Nutr Metab. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-017-0175-5

Vargas S, Romance R. 2018. Efficacy of ketogenic diet on body composition during resistance training in trained men: a randomized controlled trial. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. doi: 10.1186/s12970-018-0236-9