Linguistic Landscape of HSI Campuses

LL of HSI Campuses Survey Results

Thank you to all of the participants who were willing to spend some time answering the survey questions. After some demographic details, this page contains all of the results (with some discussion) from the 50 responses that were collected from 50 HSIs.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Target Population of HSIs

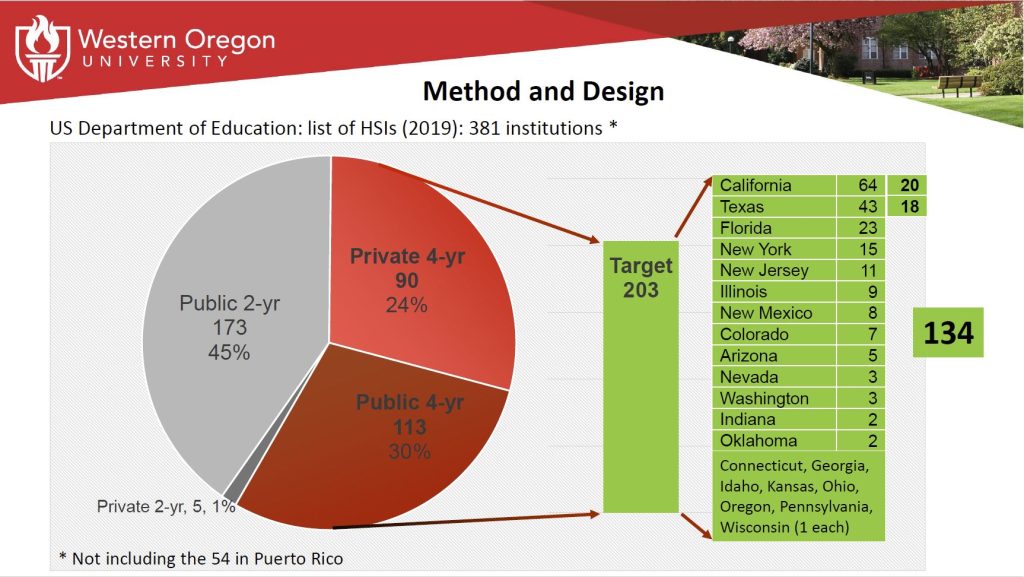

How many HSIs are there? When we started this project in the spring and fall of 2021, we relied on the most current list of HSIs (2018-19 and Fall 2019) from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2020 Digest, Table 312.40. Enrollment and degrees conferred in Hispanic-serving institutions, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/2020menu_tables.asp). This table contains information regarding 435 HSIs, categorized by institutional type (public/private; 4yr/2yr), location, enrollment, etc. We used this data to create our target list of HSIs for the survey. Because the linguistic context in Puerto Rico is very different from that of the mainland US, we excluded the 54 institutions there from this study of the Linguistic Landscape of HSIs. Note: this data does not include Private for-profit institutions.

The above numbers for HSIs from that time period and the previous years are significantly smaller than the numbers given in Garcia (2019), who obtained her data from Excelencia in Education (https://www.edexcelencia.org). Their data lists 539 HSIs (2018-19) and 569 (2019-20) and was drawn from U.S. Department of Education, NCES, IPEDS, 1994-2021 Fall Enrollment and Institutional Characteristics Surveys (https://www.edexcelencia.org/research/publications/evolution-hsis-over-28-years). Though we have not verified the cause of this discrepancy, we suggest that it is due to our not including Private for-profit institutions. NCES data for 2019-20 list 352 in this category, though it seems unlikely that nearly 100 of these are HSIs. While the difference between 435 and 539 (even adjusted for Private for-profits) is quite large, we are confident that our target population, shown below, is representative of mainland US HSIs.

Our target institutions were Public and Private 4-yr universities in the mainland US: n=203. Given the large numbers of HSIs in California and Texas, we didn’t want surveys from these states to skew data toward their contexts, so we reduced the targets there from 64 and 43 to 20 and 18, respectively. Thus, the final target population was 134 HSIs, as shown in Figure 1.

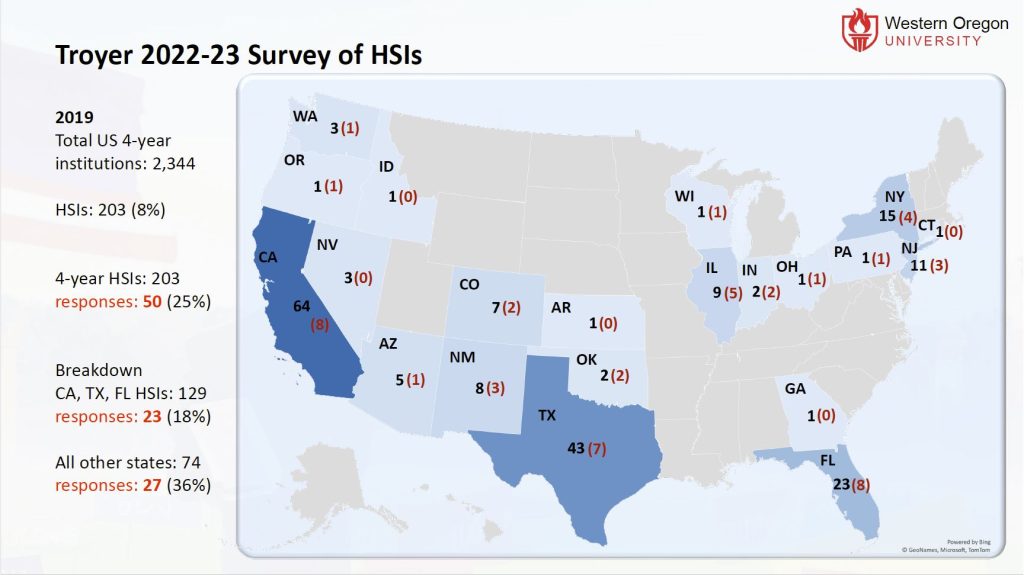

Figure 2 contains our response rates. For a broad comparison, NCES (IPEDS Data Explorer 2019-20) lists 2,344 4-yr institutions in the US in 2019-20, not including Private for-profits; thus, approximately 8% of these institutions were designated HSIs at the time. We state this percentage to counter anecdotal claims from members of the higher education establishment that soon all universities will be HSIs–while the percentage of universities that are HSIs is certainly growing, we must acknowledge that they are and will remain a minority for the foreseeable future and that racial, ethnic, social class, and other geographic and demographic factors must be addressed if we are to establish equitable methods for providing access to post-secondary education to minority populations.

In Figure 2, the numbers in black are the numbers of HSIs in the state as listed in our data set. The numbers in parentheses and red font are the completed survey responses that we received. Of the target 203 US 4-year Public and Private not-for-profit HSIs, we obtained 50 responses–25%. Grouping together the three states with the largest numbers of HSIs (CA, TX, and FL) our response rate was 18% in those contexts while for all other states the response rate was 36%.

Results

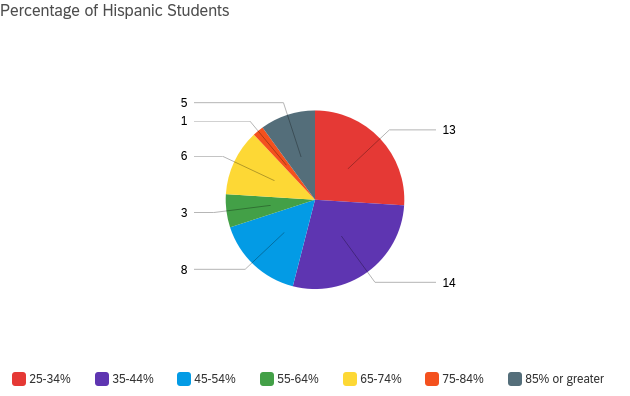

Figure 3 breaks down the 50 responses by the percentage of Hispanic students at the institutions. More than half of the responses (n=27) were from institutions that enrolled 25to 44% Hispanic students; 8 of the universities surveyed had approximately 50% Hispanic students; institutions with higher percentages were also well-represented with 5 having greater than 85% Hispanic students. Note: in the US racial/ethnic identity is self-reported by students during the university admissions process, with ‘white Hispanic (or Latino) being one of the optional choices. These percentages were chosen by the respondents; thus, we assume that participants consulted their respective offices of institutional research to obtain accurate percentages–we have not compared these self-reports to the NCES data tables that we used to create our target list of HSIs.

Our target respondents were initially university administrators who were directly connected to HSI or Title V offices, initiative, or missions or administrators connected to offices of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, etc. We quickly discovered that many institutions lack these resources or, despite our detailed searches of institutional websites, they are not well-represented or accessible on the university webpages. Thus, we expanded to more general administrators (Deans, Provosts, Coordinators, etc.). After several rounds of emails, phone calls, and voice messages over several months, we reached out to faculty in Spanish, Modern Languages, and Linguistics programs. The lists below contain the roles of survey participants, then number of responses from each category, and the job titles that they provided (duplicate titles were only listed one time). Note: as per the Informed Consent agreement, approved by WOU’s Institutional Research Board (IRB), all respondents’ personal information is confidential, and all results will be reported in regional or other aggregates in order to maintain this confidentiality.

List of Respondent Roles and Titles

- HSI or DEI Administrators/Staff (8 respondents): Hispanic Student Center Administrative Assistant; Coordinator for Hispanic Community Outreach; Title V Director, Assistant Vice Provost, Hispanic Serving Institution Initiatives; Chief Diversity Equity & Inclusion Officer; Executive Director HSI Initiatives; Director of Latino/a Student Initiatives; Director, TRIO SSS & Title V grant

- Professors (20 respondents): Professor of Linguistics, Head of the Spanish Program, Professor of Spanish, Associate Professor, Associate Professor of Spanish, Assistant Professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature, Assistant Professor, Lecturer, Professor of Hispanic Sociolinguistics

- Other Administrators (22 respondents): Associate Vice President for Academic Affairs, Vice President of Student Services/Enrollment Management, Senior Vice Chancellor, Executive Director of Academic Effectiveness, Grant Coordinator, Associate Dean of Faculty, VP for Information and Technology, Director of Student Affairs, Senior Admission Counselor, Interim Campus Director, STEM Resources Development Coordinator, Executive Director of Community Outreach and Services, Dean for Organizational Learning, Provost, Vice President and Dean of Students, Assistant Dean, Interim Campus Director, Associate Vice President for Institutional Effectiveness, Program Director, Dean College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Associate Provost, Associate Dean of Student Life, Executive Director of Grants and Strategic Initiatives

In some of the results we have categorized responses according to participant roles because the differences in perspective were significant.

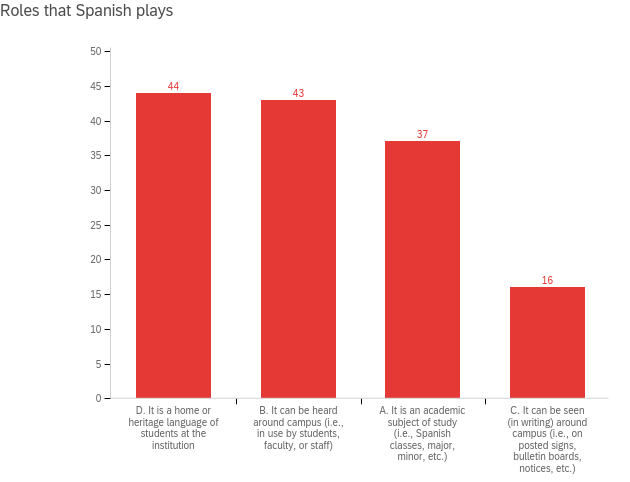

Roles that Spanish Plays

Item 3 of the survey asked respondents to indicate the roles that the Spanish language plays on their campus with the following four options (or no response) available. As Figure 4 demonstrates, at 85% of the campuses, Spanish was reported to be a home or heritage language of students that could be heard around campus. Surprisingly (for us), only 37 of 50 responses indicated that Spanish is an academic subject of study. Only 32% of responses reported that Spanish can be seen in writing around their campus.

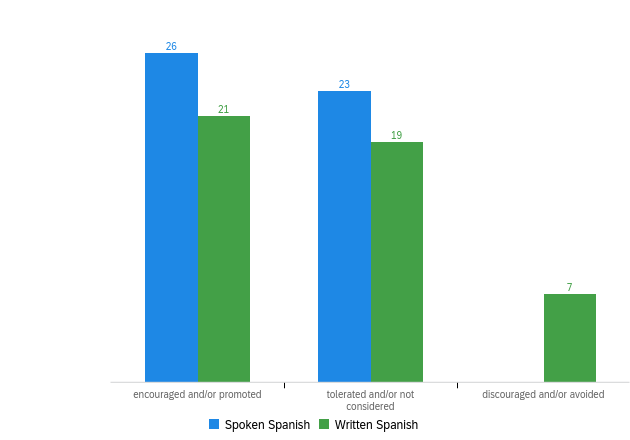

Attitudes toward Public use of Spanish

In order to assess linguistic ideologies, participants were asked to characterize the general attitude toward the use of Spanish in public on campus while recognizing that this is a subjective, highly generalized question (item 4). Each subsection of the survey contained space for open-ended responses where participants could clarify and add comments–these are addressed in the qualitative analysis. Figure 5 demonstrates that in all cases, spoken Spanish is more acceptable than written Spanish and these uses are only encouraged and/or promoted at around half of the HSIs. While none of the responses indicated that spoken Spanish is discouraged and/or avoided, it is troubling (from our perspective) that at 7 HSIs (14%) written Spanish was considered to be unacceptable. Furthermore, at nearly half of these 4-yr university HSIs, Spanish was considered by the respondents to be merely tolerated and/or not considered.

Responses to this item were also categorized according to institutional status (Public vs. Private) and percent of Hispanic student enrollment.

- At Private institutions and those with >55% Hispanic enrollment, selection of ‘Encouraged / Promoted’ was more prevalent, while selection of ‘Discouraged / Avoided’ was less prevalent.

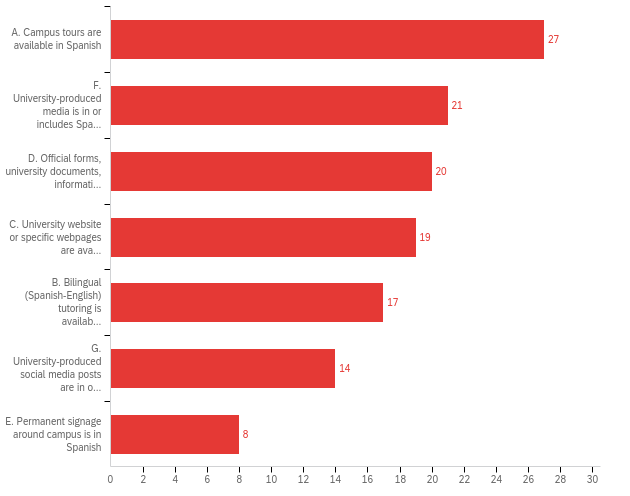

Spanish Language Services on Campus

Item 5 asked respondents to indicate the kinds of language services (if any) that their university provided that are aimed Hispanic students or other Spanish speakers. As Figure 6 shows, just over half of the HSIs surveyed offered campus tours in Spanish, and that was the most frequent language-related accommodation provided for Hispanic/Latino students. This service was followed in decreasing frequency by Spanish in university media, official forms and documents, webpages, bilingual tutoring, and social media posts. Most significant from a Linguistic Landscape perspective was that the least frequently indicated accommodation was permanent signage in Spanish with only 8 institutions (16%) selecting this option.

Responses to this item were also categorized according to institutional status (Public vs. Private) and percent of Hispanic student enrollment.

- Private institutions (17) reported offering these services nearly twice as much as Public institutions (33).

- Institutions with >55% Hispanic enrollment reported far more bilingual tutoring than those with <55%.

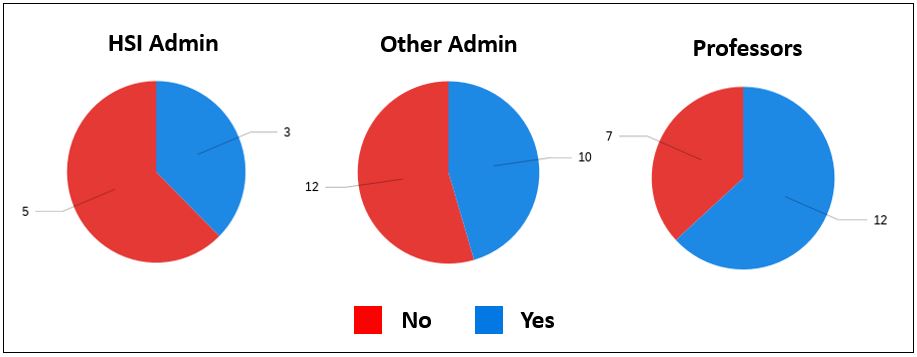

Awareness of Linguistic Landscape Studies

Speaking of the Linguistic Landscape, item 7 asked participants whether or not they had heard of the term ‘Linguistic Landscape’ to refer to the presence of and choices regarding languages that are seen and heard in a public spaces such as that seen on signs, advertisements, storefronts, bulletin boards or on media or heard in spoken use in public places and at events. According to these results, administrators who oversee HSI or related offices are the least aware that there is a field of study that encompasses language in the public sphere. Fewer than half of the other administrators had heard of LL studies, but among professors of languages and linguistics, 12 of 19 (one respondent skipped the question) reported having heard of LL studies.

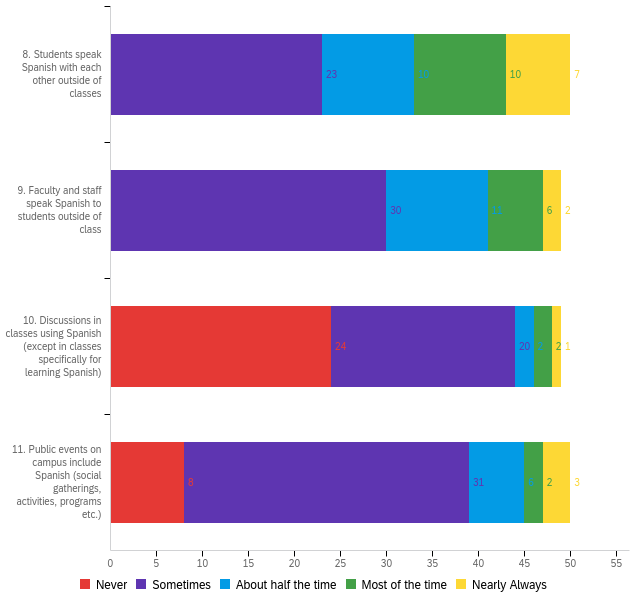

Frequency of Spoken Spanish on Campus

Items 8-11 of the survey asked participants to estimate the frequency with which spoken Spanish is present on their campus. While there is a lot of variation in the results for this item, and we suspect that the context (percentage of Hispanic students on the campus) plays an important role, these results point to a common situation on most HSI campuses in which Spanish is acceptable for informal situations, but does not have the same status or appeal for more official purposes. We contend that when a language that is shared by a significant percentage of a group (i.e., students, faculty, administrators, stakeholders of a university) is predominantly used only for informal purposes and is not sanctioned or widely acknowledged for official use, it reflects standard and monolingual language ideologies that subvert the promotion of bi- and multilingualism.

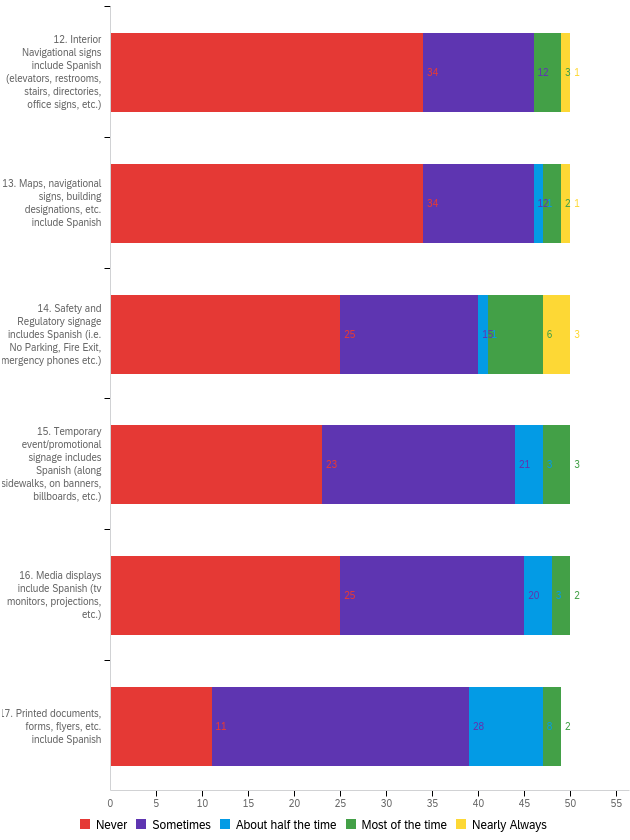

Frequency of Written Spanish in Public Displays on Campus

Items 12 to 17 asked participants to estimate the frequency of written Spanish across several registers of public language use from interior signage, to different outdoor signs, to media displays, and printed documents. As Figure 9 shows, the most common uses of written Spanish in the public sphere of the campus is on printed documents. Notably, these are the least publicly visible manifestations of the LL; on the other hand, they may be considered the most official and functionally beneficial to students and their families who prefer to use Spanish.

Research in the field of Linguistic Landscape studies has consistently demonstrated the symbolic significance of public displays of language, especially in educational institutions, where as Brown (2012) points out “The state-funded school, a central civic institution, represents a deliberate and planned environment where pupils are subjected to powerful messages about language(s) from local and national authorities” (p. 281). Given the role that publicly visible language plays in raising awareness of linguistic diversity, promoting the status of minority languages, and providing authentic, functional input for language learners (all of which is attested in LL research), HSIs that do not consistently display Spanish are missing out on a relatively simple means of promoting these benefits. Likewise, the absence of a common spoken language from the visible environment can signal a lack of status or value.

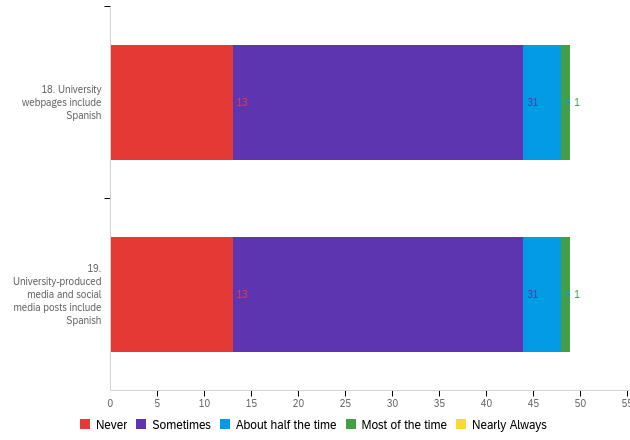

Frequency of Spanish on Webpages and Social Media Posts

Similarly, across the respondents and institutions, it was rare for participants to report the presence of Spanish on institutional webpages and social media posts with none indicating ‘nearly always’ and only one respondent choosing ‘most of the time’. 44 of the 49 responses (one participant did not answer these items) reported never or only sometimes encountering Spanish in these electronic registers.

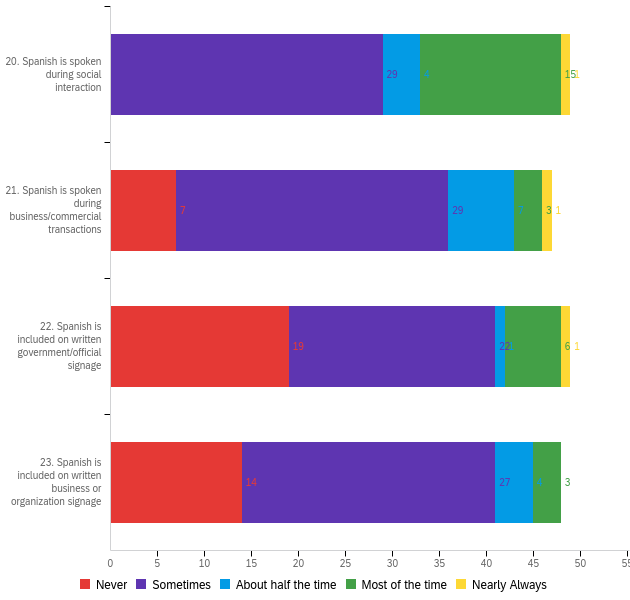

Frequency of Spanish in Public Off-campus

In order to determine the degree to which the presence of Spanish on HSI campuses is similar to that of the local context that surrounds the campus, we asked participants to estimate the frequency of spoken and written Spanish outside of the university. While it is likely that in contexts in which an HSI has more than 65% Hispanic students Spanish will be heard and seen more frequently, and we have not broken down the results along these lines, in aggregate, it appears that item 20 is similar to items 8 and 9 above (informal situations on campus) while item 21 is similar to item 11 (public events). Keeping in mind that these responses are estimations, not empirical studies, we can may hesitantly note that items 22 and 23 (Spanish on governmental and private business/organization signage respectively) was described as ‘never’ present less than on the HSI campuses, and reports of the language being ‘sometimes’ present were more frequent than in any of the physical locations on campuses. This data suggests that Spanish is seen more frequently in public around campus than on campus. Garcia (2019) advocates for increased experiential learning and community connections for HSIs, and in our experience, many universities have as part of their mission, the goal of connecting students and scholarly activities to the local community (e.g. https://wou.edu/planning/mission-vision-values-purpose/). In this regard, we suggest that HSIs seek to display at least as much Spanish on campus as students would experience off campus; when the opposite is the case, one may infer again that Spanish is not an acceptable language for an institution of higher education.

Incentives for Employees to Use Spanish with Students who Prefer it

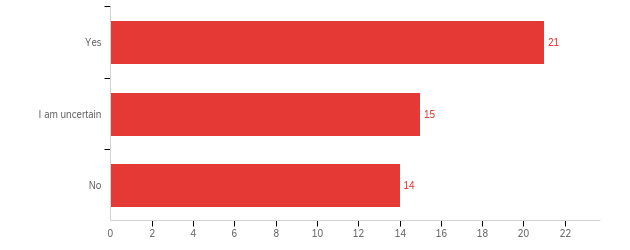

Item 25 asked “Does your institution actively recruit, provide incentives for, and/or encourage the use of Spanish by employees when they interact with students who, if given the choice, would prefer to use Spanish during interactions?” As Figure 12 shows, 42% of the respondents responded ‘yes’, 28% indicated ‘no’, and the remainder we uncertain whether such policies exist.

Thus far in this report of results, I have not included responses to the optional, open-ended items where participants could write clarifying comments. In most of these cases, a section of related questions was followed by an opportunity for comments. For participants who responded ‘no’ to item 25, the survey prompted them with “Since you answered ‘no’ to the previous question, please briefly indicate a reason why. For example, it may be that a majority of your employees are already bilingual or it may be that institutional leaders have simply not considered the practice or one or more other reasons such as seeking to discourage the use of Spanish.” I have arranged the responses, thematically, top to bottom, from those that report bilingualism is taken for granted and not compensated (3) to those indicating the practice has not been considered (5) to those that indicate a more negative stance toward the encouragement of bilingual practices (4).

Open-ended responses to automatic prompt following a response of ‘no’ to item 24.

- Being Spanish/English bilingual is definitely taken for granted. At times students are used as interpreters by administrative figures w/o compensation.

- Bilingualism is assumed but no efforts made to encourage or formalize or account for

- There is a large number of staff that is bilingual. It is not that it is discourage, it is a priority for few people not an institutional practice.

- I don’t think they contemplate the use of Spanish (as neither negative nor positive), it’s not something they pay attention to.

- To my knowledge, institutional leaders have not considered the practice.

- I think institutional leaders have not considered it

- Not considered

- Not considered

- There is no visible encouragement for the use of Spanish around the campuses

- Because the Admin is only HSI in the name and because of the federal money associated with it.

- Our institution recruits and hires but cannot retain folks because 1) there is no compensation (incentives) for providing services in Spanish 2) Spanish is not discouraged per se, but monolinguals get in their feels about being “excluded” and 3) the bias against Spanish-speakers is a constant source of microaggressions, etc. so people leave the work environment.

- Traditional Anglo culture.

Language Policies on Campus

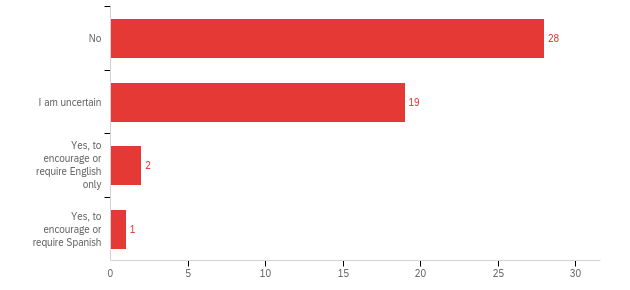

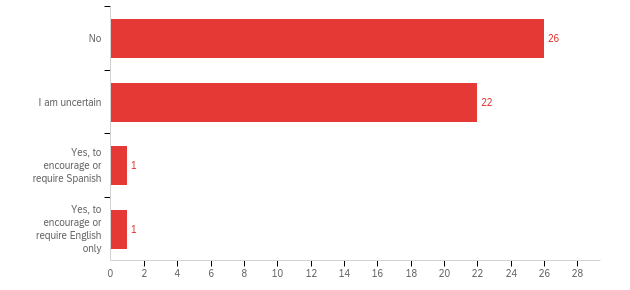

Items 26 and 27 asked participants whether their university had policies regarding the choice of language for official documents and forms and for visible signage and postings on campus. While an average of 41% of respondents were uncertain about the existence of such policies, just over half of the participants indicated there are no policies. Two of the HSIs reportedly have English only policies for official documents and forms while one has policies to encourage Spanish. Similarly for signage, only one institution had policies to encourage Spanish while one required English only. To the degree that institutional policies reflect ideologies, it appears that among these HSIs, there is little official sanctioning and encouragement for bilingual practices that would elevate the status of Spanish. Context plays an important role, however, and it is possible that at institutions where bilingualism is the norm, there is no perceived need to promote the use of Spanish through official language policies.

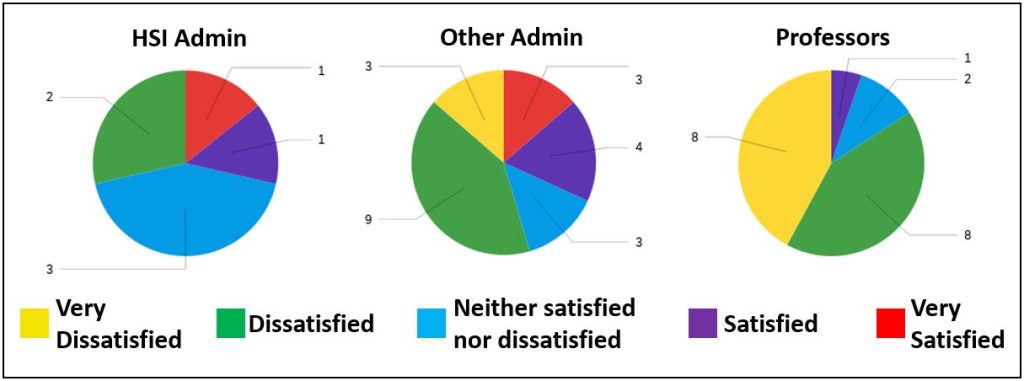

Satisfaction with Spanish-English Bilingualism and the use of Spanish on Campus

Item 28 asked participants “As an HSI leader on your campus, do you feel satisfied with your institution’s approach to Spanish-English bilingualism and the use of Spanish in public on campus?” The responses to this question were very different across the three participant roles: HSI administrators, Other administrators, and faculty. While one HSI administrator and one faculty member did not answer this question, it is evident that HSI administrators viewed their bilingualism far more favorably than other administrators and that faculty in language teaching and linguistics were the least satisfied. However, another interpretation follows from the afore mentioned difficulty in identifying HSI-specific offices and administrators on many campuses. It may be that on campuses where these departments and personnel are present, accessible, and responsive, there is an overall greater satisfaction. On the other hand, on campuses at which these resources were not accessible and where other administrators were uninterested in participating in a survey regarding HSIs status and Spanish (thus, leading us to recruit faculty as participants), there is far less satisfaction in these regards. This interpretation is conjectural though and would need to be verified by asking the same question of members of all three roles at each institution surveyed.

Responses to this item were also categorized according to institutional status (Public vs. Private).

- Participants at private institutions reported higher levels of satisfaction.

Additional Qualitative Results

Following items 3-5, the survey contained the first of three prompts that appeared as “If you would like to qualify, clarify, comment on, or add to any of the above items and/or your answers, please respond here.” Listed below are the answers of all 20 respondents who submitted a directly relevant answer (2 responses were excluded). No changes have been made to responses except to redact information that would identify an institution or individual. I have coded these answers according to their assessment of the institution’s current bilingual practices according to these categories: sufficient, inconsistent, improving, ignored, insufficient.

Current bilingual practices are…

Sufficient (1)

- [redacted institution name] is a bilingual institution but not in traditional fashion. For us, bilingual meats that faculty and staff are bilingual and can address the students in class and administrative functions in a way that is the most effective. Instruction at [redacted] is in English

Inconsistent (13)

- It also depends on the college. SOme do more than others

- Some areas of our campus are better than others in providing additional materials/alternative materials in spanish.

- Despite the high percentage of students who identify as Latinx and who perhaps speak Spanish, and the number of faculty and staff that work on our campus, very few of the permanent signage around campus is in Spanish.

- I’ve only seen a couple of social media posts in Spanish. Our translation students have worked for some of the tours with parents (it’s not a permanent service)

- Some of the services that I did not select are because these things exist, but only in a limited manner.

- When I asked about campus tours in Spanish, I was told that they would have to be requested on an individual basis, but that they’re not offered on a regular basis. Spanish language tours are not offered as an option on the webpage.

- Each of these indicated are in some cases but not necessarily routine or normed

- When it comes to our website we will have a few places in which documents will be in Spanish otherwise it is not very present

- Basically no services available in Spanish; our study of signage on campus shows that Spanish is used in writing for two purposes: 1) advertising a limited number of talks / presentations / events in Spanish, from academic units like Modern Languages and [redacted] Research Institute; and in directives “no entrar,” “no tirar granos de cafe” etc.

- We have many of the above, but it’s all very spoty and not consistent. We also over-use our bilingual students to provide language services rather than institutionalize the skills via its professionals.

- These Spanish services are practiced occasionally, but not consistently.

- These Spanish services are most evident at our [redacted] Regional campus, and to a lesser extent on our other campuses

- Tours (we allow for tour groups to specify is they would like a Spanish speaker present, however this can only be offered if a staff person is avaialble); University media (we have [redacted] news en Espanol, this is one of a few outlets where news/content from [redacted] is in Spanish)

Improving (3)

- Websites, forms, media, and social media are not commonly available in Spanish, but are increasingly so especially when the intended or at least an expected possible audience includes family members of students or potential students.

- some of these answers reflect recent strides to include what we selected

- We are currently reviewing and translating more university materials.

Insufficient (3)

- We do not have enough representation of the Spanish language in our institution. The representation is mostly carried by Spanish speaking faculty and staff within their programs or classes- which are not that many. Not institutionalized at all. However, this issue has been brought up to the President.

- College is experiencing transition. Over the last 10 years, the number of Latinos in the County has grown. We still have some traditional employees who struggle with others speaking other languages.

- There are limited to no options in Spanish on our campus. There is a Spanish supporters section for new student orientation but that is about all. The university as a whole does not have a practice of using Spanish on websites, documents, signage, offerings etc.

- The Spanish program is not supported by the administration, and we don’t have a language requirement. Although we have so many Heritage students, most of them are not fluent and don’t write or read Spanish

Optional comments following items 8 to 24

These are also categorized thematically but with an additional category for several responses indicating the difficulty of assessing the degree of Spanish use on campus. All eleven responses are listed below.

Use of Spanish in the linguistic landscape of campus is…

Inconsistent (4)

- Some departments do it more than others.

- Some departments make an effort to do this at the dept level but much less so at the university level.

- Most of events in Spanish are from the Spanish program

- In some exchanges, Spanish is heard being used. It all depends on the context and the speakers (and how comfortable they feel speaking Spanish).

Improving (1)

- The University is currently engaged in reviewing all materials and ensuring that specific web pages and materials are available in Spanish.

Insufficient (2)

- There are neighborhoods in [redacted city name] that are overwhelmingly Spanish-speaking, including those immediately adjacent to campus. The difference between language use in the community and on campus is stark.

- Again, our adoption of any Spanish language use is spotty and inconsistent, and when it is part of staff duties, it’s inequitably practiced and uncompensated. They will disrespect Spanish speakers and tokenize them at the same time.

Difficulty of Assessing the LL (4)

- It is hard to know for certain.

- There were some items left blank because I was unsure

- Some of the questions are really challenging to answer, because one would likely not know all that occurs during each of these scenarios. And I assume a high level of leadership at the university and would still have a hard time knowing this.

- I have selected sometimes in responses becuase it happens in pockets, I’m not fully aware of all areas of the campus so I selected the best guess.

Optional comments following items 26 to 28

There were 18 responses to the final optional item (#29 on the survey)–one was excluded for lack of clarity/relevance.

Current bilingual practices are…

Sufficient (1)

- While Spanish is the language most frequently spoken on campus after English, Arabic, Portuguese, and Urdu are spoken almost as much and there are several other languages that often are spoken too. As a consequence, despite our HSI status, of which we are very proud, we are not and do not foresee ourselves as being in a position to privilege Spanish over these other languages. Rather, faculty and staff badges and name plates typically indicate which languages are spoken by the individuals, students are encouraged to speak to employees in the indicated languages if they wish, and many enrollment and orientation forms and programs are produced in the most commonly spoken languages other than English.

Improving (6)

- We have plans in our new strategic plan

- There is lots to improve on, although we have made some good strides over the past year.

- We recognize that more is necessary.

- We recently became an HSI, this journey is just a beginning. You are giving me a lot of ideas as to how we can be serving students better. Thank you.

- At this moment, we are seeing greater support for the use of Spanish on our campus, but we are just at the beginning stages of finding what makes the most sense for us as an institution

- As a relatively newly-designated HSI, we are still in the process of learning what adjustments would be most beneficial to students who prefer communicating in Spanish.

Insufficient (10)

- I’m very dissatisfied with the institutional approach to Spanish-English bilingualism, and I am concerned about the many languages (and speakers) other than Spanish(-speakers) that are being neglected.

- There is a problem when administration encourages foreign language departments to offer their course content in English.

- Most bilingual universities in my experience offer free or subsidised classes on campus. Not at [redacted]

- I would like to see more encouragement from the institution promoting the use of Spanish and valuing its contribution to society.

- It seems like they promote heritage languages when they depict the university as being diverse but then do things like cut ‘foreign language’ requirements, thereby precipitating a drop in enrollment in Spanish and underfund our Spanish as a Heritage Language program

- I would like to see more signage in Spanish around campus.

- The institution lacks of a clear plan of bilingualism across campus. The fact we use Spanish does not mean that we are a fully delivered bilingual institution

- The don’t support the Spanish program. We are in [redacted] and have only 3 Tenured faculty. Students of Latino/a Studies are not encourage either to learn the language

- I used to be very dissatisfied, but luckily I have been able to influence (together with others) the direction of the institution and push for more and better, but the resistance is strong and Spanish continues to be marginalized, disrespected and therefore discouraged. This survey was triggering for me because it brought up all the instances in which Spanish has been treated as a second-class language, Spanish-speaking professionals as 2nd class faculty/staff. It’s been toxic.

- We can do better. This survey is helping me to realize that we can do better.

Statistically Significant Correlations

Using the Qualtrics platform, correlations between several items were sought. For correlations that used a Chi-Square Test, the following values are given in parentheses (P-Value, Cramer’s V Effect Size, Sample Size).

Item 28. Degree of satisfaction with institutional approach to Spanish/English bilingualism on campus was compared to all other variables. The following relationships were determined to have a strong statistically significant relationship.

- Item 8. Frequency of students speaking Spanish with each other outside of classes

- Item 11. Frequency of Spanish being spoken at public events on campus

- Item 17. Frequency of printed documents in Spanish

- Item 4 (Written). Attitudes toward Written Spanish in the LL on campus (0.0456, 0.419, 45)

- Item 25. Recruitment / incentives for bilingual staff (0.0306, 0.42, 48)*

- * Private institutions and those with <55% Hispanic enrollment were more likely to recruit/incentivize.

Item 2. % of Hispanic student enrollment was also compared to all other variables. The following relationships were determined to have a strong statistically significant relationship.

- Item 8. Frequency of students speaking Spanish with each other outside of classes

- Item 10. Frequency of discussions in classes using Spanish

- Item 11. Frequency of Spanish being spoken at public events on campus

- Item 12. Frequency of interior navigational signs that include Spanish

- Item 13. Frequency of maps, navigational signs, building designations, etc. that include Spanish

- Item 15. Frequency of temporary event/promotional signage that includes Spanish

- Item 16. Frequency of media displays that include Spanish

- Item 17. Frequency of printed documents in Spanish

- Item 19. Frequency of university-produced media and social media posts that include Spanish

- Item 23. Frequency of Spanish included on written business or organization signage off campus

References

Garcia, G. A. 2019. Becoming Hispanic-Serving Institutions: Opportunities for Colleges and Universities. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Brown, K. D. (2012). The linguistic landscape of educational spaces: Language revitalization and schools in Southeastern Estonia. In D. Gorter, H. F. Marten, & L. V. Mensel (Eds.), Minority Languages in the Linguistic Landscape (pp. 281–298). Palgrave Macmillan.